When Beverly Jenkins started reading romance, she recalls in this clip from Love Between the Covers, “there was nothing for somebody who looked like me. There were articles back then that said Black women couldn’t do historicals, couldn’t do romance fiction. But you know, they’ve been telling us that for two hundred years about just about anything.”

When does the story of African American romance fiction begin? How has the genre evolved, both separately from and in dialogue with, other varieties of American women’s writing? How have characters of color shaped the history of popular romance, from 19th-century sentimental heroines to E. M. Hull’s scandalous Sheikh Abdul ben Hassan, the character who made Rudolph Valentino famous? How have women authors of color used the romance genre to reimagine love and desire, history and resilience, the challenges of the present and hope for the future?

Popular Romance Project scholar Darlene Clark Hine says that the “backstory” of African American romance begins before emancipation, when enslaved Black women faced “the ever-present reality of sale, of disruption, of losing these children and these husbands—the rupture of the family, which was the biggest threat of them all.” Listen to her account of how people “tried to be together, even if it was just for a moment” in the love stories told in the face of this threat reality—and sung, in the words of folk songs and blues. For fictional visions of romantic and familial love resisting the terror of slavery, check out Beverly Jenkins’s classic Underground Railroad romance Indigo and her pirate romance Captured, based in part on the actual multiracial crew of the pirate ship Whydah. Find out more about the Whydah with this timeline from National Geographic.

“Why does the slave ever love? Why allow the tendrils of the heart to twine around objects which may at any moment be wrenched away by the hand of violence?”

In her classic autobiographical novel, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Harriet Jacobs asks a piercing question: “Why does the slave ever love?” Read her remarkable story of bravery, secrecy, and escape in this online edition of the book, and watch this University of North Carolina documentary about her life and work, now richly documented by the discovery of Jacob’s personal papers and letters.

For decades after the Civil War, says Popular Romance Project scholar Darlene Clark Hine, there was “an obsession with family reconstruction”: with marriages that were finally sanctioned by law; with family gatherings; with the search for lost children and relatives. That obsession echoes in the themes of family-building and reconnection in Beverly Jenkins’s contemporary “Blessings” novels, which sometimes feature the descendants of beloved characters and settings from her historical romances.

Iola Leroy, or Shadows Uplifted, one of the novels in the Reconstructioc-era sentimental tradition

“So, from 1877 to the turn of the century, you have a period of increasing disfranchisement for African Americans. The gains of Reconstruction are being aggressively pushed back against throughout the country; but you have a whole set of African American women writers who write incredibly optimistic Victorian love plots, marriage plots.”

As the civil rights gains of Reconstruction were rolled back from the late 1870s to the end of the 1890s, says project scholar William Gleason, African American writers wrote “incredibly optimistic” love stories, enabling middle-class Black women not just to escape, temporarily, the trials of the present but also to take heart and “reimagine the future.”

Enduring stereotypes cloud the perception of Black women as romance heroines, and of Black couples as intimate, loving, and mutually vulnerable. Here's Darlene Clark Hine on perceptions of blackness.

“It is really hard, and has been, for a lot of white Americans to think of Black women as beautiful...”

“The images in the video—pictures from the early days of their courtship, candid shots from backstage at political events, moments of the couple with their daughters—are the stuff of good romance.”

Conseula Francis spots one vivid exception to this rule: the campaign photos, anniversary videos, and other representations of Michelle and Barack Obama as a couple. You can also check out #BlackOutDay, a campaign to change perceptions of blackness.

To push back against racist stereotypes, late-nineteenth and early twentieth-century Black women activists embraced Victorian social proprieties, cultivating what Harvard historian Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham famously dubbed “the politics of respectability.” Myisha Cherry says respectability politics have never gone away.

“Instead of moral excellence being a possibility for us all, politics of respectability places the burden of virtue on the oppressed and lets the oppressor off the hook. ”

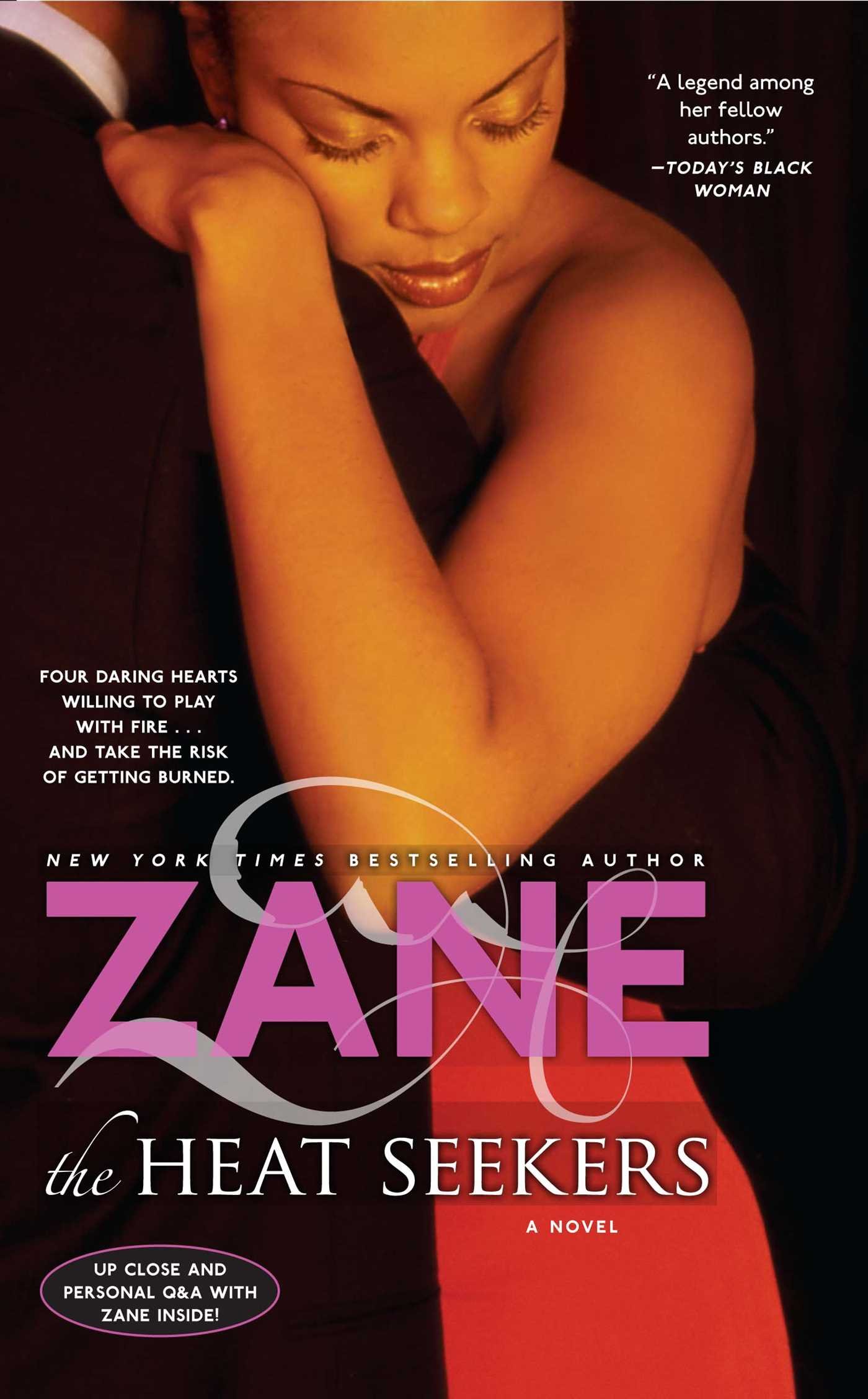

But Black erotic romance author Zane works hard to shake off respectability for herself and her readers, without losing sight of love, according to Conseula Francis in her Popular Romance Project blog post "Zane and respectability."

“She writes unapologetically about sex, intends to get you all hot and bothered, and believes she is helping to free black women from inhibitions created by what scholar Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham calls “the politics of respectability.””

From the 1921 adaptation of The Sheik with Rudolph Valentino and Agnes Ayres

Across the 1920s, the most scandalous, unrespectable love story around was E. M. Hull’s abduction romance The Sheik (1919). British heroine Diana Mayo was definitely white, but what race, really, was the hero, Sheikh Ahmed ben Hassan? Australian Historian Hsu-Ming Teo looks at how differently British and American audiences interpreted the book and the silent film in her article in the Journal of Popular Romance Studies “Historicizing The Sheik: Comparisons of the British Novel and the American Film".

“In many ways, the Middle East is represented as the West’s “inferior Other”—a place where gender relations are deeply unequal, women have few rights or professional opportunities, and Muslim men are shown to be aggressive, ruthless, oversexed, and sometimes cruel in their treatment of women.”

Sheikh romances draw on a centuries-old tradition of Orientalist love stories, writes Hsu-Ming Teo, whose cultural history Desert Passions begins in all the way back in the 12th century. American authors started writing them in the 1980s, she explains at the Popular Romance Project. sometimes engaging real-world history in fascinating ways

See also: "The Sheik and the Vixen," Hsu-Ming Teo, blog post at The Popular Romance Project

Gwen Osborne says that the current wave of African American romance dates back to 1992, the year that Terry McMillan’s Waiting to Exhale hit the New York Times bestseller list.

A handy timeline from RT Book Reviews pushes this history back to 1980,

But, in her blog post "Romance in black papers" at The Popular Romance Project, historian Kim Gallon says that an important earlier wave has long been forgotten: the world of Black romance stories that filled newspapers and magazines in the 1920s-30s, full of millionaires, princesses, and thrilling tales of “Brown Love.”

““The Dark Knight” challenged the common idea that African Americans lacked the capacity for romantic love, a love that has been and continues to be integrally linked with a white, bourgeois value system.”

Kim Gallon’s sleuthing turns up another forgotten bit of Black romance history: the tremendous popularity of interracial love stories in the 1930s Black press. Read an excerpt from “How Much Can You Read about Interracial Love and Sex without Getting Sore?: Readers’ Debate over Interracial Relationships in the Baltimore Afro-American.”

“Ultimately, interracial romance stories brought readers into conversation with each other and the Baltimore Afro-American to create a discourse that tied interracial romance to the African American battle for equality in the early twentieth century.”

Interracial stories frame The Brightest Day: A Juneteenth Historical Romance Anthology, one set in the years right after the Civil War, and one set among the Freedom Riders of the 1960s Civil Rights movement. Check out the USA Today Happily Ever After interview with the authors.

Although it ends on a bittersweet note, Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937) remains a favorite of Black romance readers—in fact, Kim Gallon calls it the Black feminist love story. Darlene Clark Hine agrees, and puts the novel squarely at the heart of the Black romance tradition.

“The Case:

Our contributor found an unusual 1950’s comic book at an auction, titled Negro Romance.

This was the Golden Age of comic books, when Americans voraciously consumed stories about superheroes, determined detectives and thrilling romances - yet very few featured African American characters.

Did black artists create this comic book?

And who was the intended audience? ”

In the 1950s, the Golden Age of comics, tales of Black love came to artful life in the pages of Negro Romance. Investigate the world of Black comics and click through the pages of one story, “Possessed,” with the PBS History Detectives.

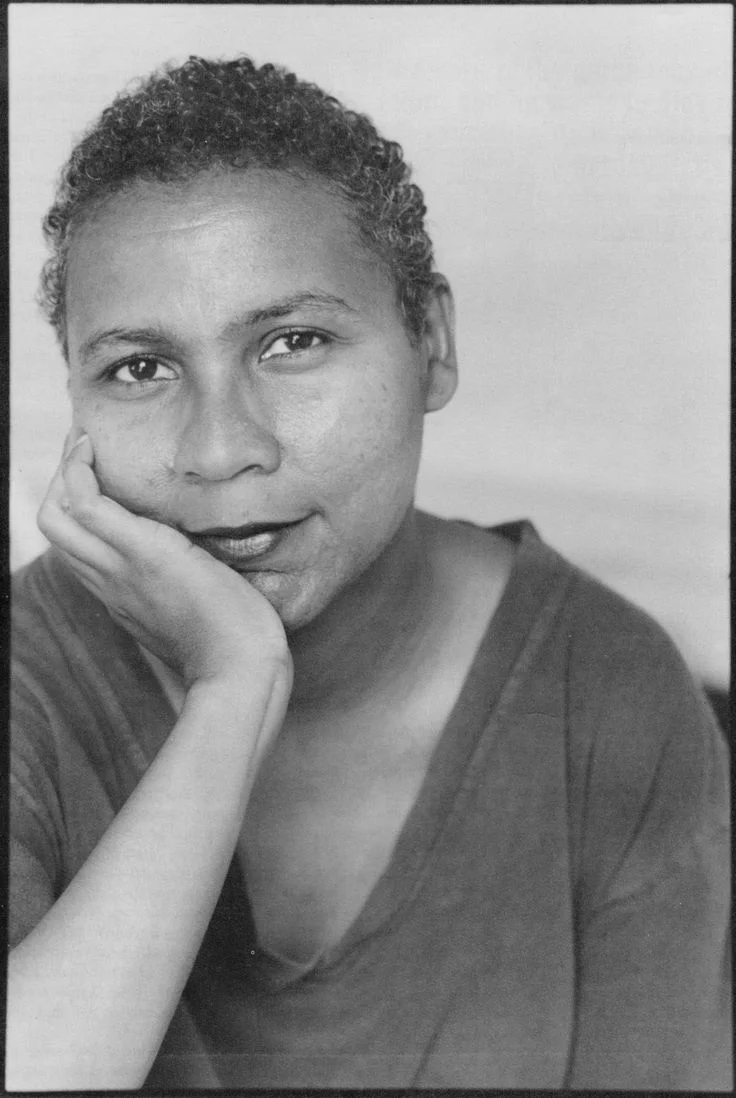

bell hooks

“In the essay “Love as the Practice of Freedom,” hooks makes a case for the need for an “ethic of love” to characterize our efforts toward positive change (1994: 289-298). She tells us that “the moment we choose to love we begin to move toward freedom, to act in ways that liberate ourselves and others” (1994: 298)... So what is so special about love? Why does she seem to thikn that it must serve as the foundation for our political efforts against domination?”

Activist and philosopher bell hooks grew up reading Harlequin romances, she recalls in Communion: the Female Search for Love, and those stories of love’s “transformative power” still resonate in her essay “Love as the Practice of Freedom.” Marquette University philosopher Michael Monahan explores hooks’s theory and politics of love.

“It’s easy to say this is a celebration of Asian masculinity and sexuality. It’s about time.

But then I also wondered, is this a desired outcome? Would Asian men feel they are getting some equal treatment in mainstream media now that they’re starting to be depicted as attractive romantic heroes who actually get the girl?”

“You have a lot of people who may not have wanted to buy an African American book with an African American cover,” Beverly Jenkins notes in Love Between the Covers. Authors of other multicultural romances face similar challenges—but not identical ones. Historical romance author Jeannie Lin says that Asian heroes rarely show up on book covers—and when they do, is it a “a celebration of Asian masculinity and sexuality” or just a new form of objectification?

“But I think whether you’re even talking Latino books or African- American books, my thought has always been is that when you brand them like that it’s almost like saying, “Okay. This is for you, but not for you.” And my experience was with Harlequin, they never branded my books like that.”

When Kensington Publishing launched Encanto, they wanted to represent the full “rainbow of cultures” that make up Latina romance, says author Caridad Piñeiro. The “difficult experiment” for Kensington—and for other publishers, like Harlequin—hasn’t been about finding authors; it’s been about how to brand the novels for potential readers.

In the romance community, group blogs have long let readers and authors connect and spread the word about new titles and writers of interest. One of the latest and liveliest is Saris and Stories, where seven U. S. based Indian authors write about romance fiction, Bollywood films, Indian culture, and diversity in romance.

In 2015 the hashtag campaign #WeNeedDiverseRomance brought fresh attention to romance authors and characters of color. Buy the T-shirt here, and wear it while you browse the links, lists, new releases, publisher announcements, and gorgeous covers at the Women of Color in Romance Tumblr. Check out the #WeNeedDiverseRomance tag on Twitter!